|

WW2 Defences in Caithness By Andrew Guttridge (Editorial Note. The following text is the second part of an article dealing with WW2 Defences in Caithness. The first part, dealing with the ground defences, appeared in the 2001 edition of the Bulletin. A copy of the first part may be obtained from the Author, or from the Editor of this Bulletin). [Transcriber's note: The photos in the Bulletin were in black & white; some did not print too well. As the original colour photos were available, both the editor at the time and the current editor have agreed that these could be reproduced here instead. Nothing else in the Bulletin article has been changed.] Air Defences The threat of aerial attack on Caithness was very real, although its actual experience was trivial in comparison with that of other British cities later in the war. Nevertheless, during the first few months, the period of the �phoney war� in the south, the north of Britain found itself on the receiving end of some of the first German bombing raids of the war and can claim a number of the major �firsts� of the war. First German aircraft shot down over Britain (Orkney), first civilian killed (Orkney), first bomb to land on Britain (Orkney) and mainland UK (Caithness).

Of course Scapa Flow was the main target and some of the first attacks Caithness suffered were as a result of German aircraft jettisoning their bomb loads after being driven off from their main target. However, as Caithness became more extensively used as a base for Orkney defence so the Luftwaffe�s attention turned here and raids were mounted specifically against the county. RAF Wick was bombed on more than one occasion and the town of Wick itself was bombed and strafed by machine gun fire. RAF Wick�s decoy site at Sarclet was also bombed on a number of occasions by Luftwaffe pilots, mistaking it for Wick, and ships in Thurso Bay were attacked and one armed trawler, HMS Beech, was sunk just off the Bishop�s Palace at Burnside. To protect the county�s inhabitants and military bases a number of air defence measures were taken to prevent aerial attacks, these were either active defences such as airfields and anti aircraft guns or passive defences such as radar and decoys. Anti-aircraft poles and ditches can be classed as passive defences and these have been mentioned elsewhere. Active Air Defences Airfields RAF Wick Wick became a Sector Station in December 1939 with responsibility for aircraft movements from the borders to Shetland and the Western Isles. Initially the station was shared between Fighter and Coastal Commands, with fighter squadrons based here for the protection of Scapa Flow, but in October 1940 Fighter Sector HQ moved to Kirkwall leaving Wick solely to Coastal Command. The station remained thus until the end of the war, flying patrols over the North Sea and Atlantic Ocean and making long range meteorological and reconnaissance flights. The last squadron to leave Wick was No.316 on March 1946. After this the airfield reverted to civil operation which it remains to this day. The station buildings seem to have been constructed in the pre-war expansion period layout with all the station buildings being clustered together in a single area with the domestic side also being very close by. This presented an ideal target to a bomber which could do immense damage to this compact group of buildings with only a few bombs. Later stations, such as Castletown and Skitten, had their buildings widely dispersed and thus presented less of a target. Very few original wartime buildings survive at Wick, although two of the original four huge 'C' type hangars are still standing, along with the original watch office or control tower. Most of the technical and administrative buildings were prefabricated wooden hutting which survived until recent years as industrial units. A big cleanup in the late 1980s saw the whole area re-developed and all these buildings were demolished to make way for new modern industrial units. An interesting survival is the bomb and ammunition stores compound on the northern boundary. Still with their huge steel doors and protective blast walls, built as much to protect those outside from the affects of an explosion inside the store as to protect the stores from attack outside, they are a stark reminder of Wick airport's more aggressive past.

RAF Castletown Its main tasks were mainly flying coastal patrols and convoy escort, providing fighter cover for ships sailing to and from Scapa Flow and the arctic convoys. Although its career was relatively uneventful it did have its moments of excitement such as on 18 May 1944 when two Junkers 188s flew in from the north-west at zero ft. and disappeared inland. The last squadron, No.504, left Castletown in April 1944 and the station closed in mid 1945.

Today there is little to see of the airfield. The three runways and perimeter track are still there and at the northern end, near Thurdistoft farm, the gas decontamination centre, small arms range, bomb stores and parachute packing shed make up the most significant remains, although all are now in poor condition. Behind Tansfield house is the VHF transmitter site and in the grounds of Castlehill House, beside the high wall, can be found the station squash court. At the southern end are the aircraft gun testing butts, some dilapidated dispersal huts and aircraft pens which are gradually becoming just mounds of mud and on the hillside above is the Battle HQ. Castletown had an Emergency Landing Ground (ELG) situated at Brims near Crosskirk. This provided a place where aircraft could land if Castletown became unsuitable for flying for whatever reasons or over-spill accommodation for aircraft if there was not enough room at the parent station. The landing ground itself was simply a number of grass fields joined together by removing boundary walls and fences and filling in ditches. A complement of men from Castletown was billeted in nearby farmhouses and did a weekly shift, guarding the fuel dump and whatever aircraft may have been using the Emergency Landing Ground. RAF Skitten There are a number of surviving buildings at Skitten, including the original watch office and fire tender shed. The other remaining buildings are all standardised brick and concrete hutting whose function is impossible to deduce without recourse to a site plan. The runways are now gone, either by excavation or buried under building waste. Skitten is associated with two notable WW2 exploits. Perhaps the better known is Operation Freshman, the ill-fated attempt to destroy the Norsk Hydro plant near Vermork in Norway. This plant was producing deuterium (heavy water) for use in Germany's atomic weapons research programme and it was considered of paramount importance to stop this research, by whatever means, and so hinder Germany's development of atom bomb technology. In late 1942 a party of specially trained Royal Engineers arrived at Skitten under the code name 'Washington Competition' with the object of mounting a raid, with the help of the Norwegian resistance, on the plant and destroying it and its deuterium producing capability. At 17.45 on the night of 19 November, two Halifax bombers flew out from Skitten each towing a Horsa glider. On board were the Royal Engineers, eager to put their training into practice. However the raid went tragically wrong. The aircraft became lost in bad weather hundred of miles off course when their navigation malfunctioned. One Halifax, with its glider still attached, flew into a mountain killing all those onboard the plane and glider. The other Halifax lost its glider prematurely when the towrope froze and snapped. The Halifax managed to limp back to Skitten on its last drop of fuel, while the glider crash-landed many miles off course. Most of the glider crew were killed in the crash and the survivors were all quickly captured and delivered to the Gestapo. They were interrogated and eventually either shot or killed by lethal injection. The supply of deuterium was later destroyed, while in transit as it left the town, by the courageous efforts of the Norwegian resistance. The story has been more or less accurately recounted in the 1965 film 'The Heroes of Telemark' starring Kirk Douglas, and the full story can be found in the book 'Operational Freshman' by Richard Wiggan. A memorial, to the men of the 'Washington Competition' and the crew of the Halifax, was dedicated at Skitten on 5 Sept 1992. In attendance were two members of the original Norwegian resistance team that attacked the plant and eventually destroyed the heavy water cargo. In April 1943 Skitten became the base for training with the 'Highball' bomb. Highball was an offshoot of the Grand Slam bomb used against the Ruhr dams by 617 'Dambusters' Squadron. It was designed for use against shipping, primarily the Tirpitz, and although it was never used in anger, specially modified Mosquitoes of 618 Squadron (617's sister squadron) flew from Skitten to lochs on the Scottish west coast specially selected for their resemblance to the Norwegian Fjord where the Tirpitz was anchored. The raid was timed for the day before the Dams raid but problems with the weapon and delays in training the crews resulted in the project being abandoned. Dounreay Very few of the original station buildings survive, the one major exception is the control tower, slightly modified with the addition of a 'green house' control room on the roof, it now houses the Dounreay Exhibition Centre. Just across the road is a brick and concrete building that housed the 'Link Trainers'. These were early flight simulators used to teach the skills of aircraft pilotage to newly qualified pilots. Further along beside the road is the gas clothing store, the first home of the Dounreay Apprentice School, and in the fields behind can be seen a few crumbling buildings of the domestic sites. Towards the western end to the left of the road stands one of the large Stand By Set Houses which housed the large diesel electric generators which supplied the site with electricity. On the hill top behind there are the remains of the radio navigation beacon, a blind flying aid to the guide aircraft in to land at night and in conditions of poor visibility. To keep these airfields supplied with the thousands of gallons of aviation petrol they required a fuel depot was built beside the Hoy railway station near Halkirk. A rail spur was run from the main line into a compound adjacent to the track. In the compound were a pump room, office and a protected building probably a flammable store for storing oil and grease. Petrol tankers shunted into the compound would have their contents pumped up into four huge underground storage tanks in a compound on the north side of the track. Beside the pump room was a fuelling gantry where fuel bowsers from the airfields could fill up from the underground tanks to take back to the airfields and fill up their own underground storage tanks. The storage tanks were demolished many years ago but the pump-room and the protected building still stand inside the southern compound. Anti-Aircraft Batteries A number of Light Anti-aircraft (LAA) batteries of 40 mm Bofors guns were also allocated to each airfield. These battery sites were probably constructed mostly of earth and sandbags and consequently there is no visible evidence of any of these sites left today. Conversely, to the south of Wick at Tannach, the remains of two LAA batteries do still exist. These were constructed to protect the CH radar station there. A circular concrete apron with ring bolts surrounded by ready-use ammunition lockers and a range-finder housing are all that remain of the gun pits, the earth or sand bag revetment that would have protected the gun and crew having been removed. Nearby are two semi-submerged ammunition lockers and some concrete bases for Nissen huts for the crew. On Burifa Hill on Dunnet Head can be found four octagonal stepped plinths with a ring of bolts at the bottom. These were mounts for Oerlikon machine guns providing anti-aircraft protection for the Gee station here. Passive Air Defence Castletown had a night only decoy or 'Q' Site. This consisted of an elaborate light show laid out on the ground to look like a fully functional airfield when seen from above. Lamps representing runway lights, vehicles and even taxing aircraft were all simulated to give this false appearance. The whole system was controlled from a small bunker nearby. One room held the switch panel from where two airmen could turn the lights off and on as required and the other housed a small petrol-electric generator to supply the power for the lights. Castletown's 'Q'-Site control bunker can be seen beside the road between Greenland and Inkstack, a small red brick building with two large earthenware pipes protruding from the wall. The building would originally have been banked up with earth for protection and the two pipes acted as ducts through this earth bank to supply air to, and vent the exhaust from the generator.

Wick had a combined night and day decoy or 'K' Site. These were more elaborate schemes as they had to appear realistic during daylight as well as might time and had to simulate runways, perimeter tracks, buildings, aircraft, vehicles, people and every other appearance of an operational airfield.

Wick's 'K' site was situated at Sarclet just below Ulbster Hill. It was equipped with dummy Blenheim bombers, buildings were simulated with wood and canvas and even special inflatable vehicles were used. There are still some small control bunkers and personnel shelters dotted around the site and if viewed from the vantage point of Ulbster Hill the faint outlines of runways and perimeter tracks can still be made out. This site was actually bombed on a number of occasions. These decoys were more or less abandoned after the Battle of Britain when the Luftwaffe switched to night raiding in the south and they had already identified many as decoys. Radar During the early part of the war it was decided to extend the 'Chain' in the north and west of Britain. Tannach, to the south of Wick, was one such station. Others were to the south at Loth and to the west at Durness. The buildings of this station are still relatively complete and the original early war style control bunkers, massive structures designed to withstand a direct hit from a 1000 lb. bomb can be seen to the west of the Thrumster-Haster road. They comprised the transmitter (Tx) block, the receiver (Rx) block and the stand-by set block. The Tx block housed the electronic equipment that generated the radar signal and beamed it out over the Moray Firth from aerials supported from four 360 ft steel transmitter aerials situated close by. The Rx block was the 'heart' of the whole site, it housed the radar receiver equipment and the operations room. From two 240ft. wooden receiver masts, close by, the returning radar signals were picked up and fed to the control room where WAAF operators spent hours staring at their screens monitoring the movements of aircraft as they flew in and out of Tannach's area of influence, reporting all to the operations room at Wick (later Kirkwall) and sometimes causing fighters from Castletown and Wick airfields to be scrambled when a hostile 'contact' appeared on their screens. Here also was housed the calculator, a mechanical computer for determining the height and bearing of 'contacts', and also the various offices. The stand-by set block housed a large diesel generator that supplied the site with electrical power. It also contained the large tanks needed to store diesel fuel to feed the generator. Further along the road, behind Grudgehouse, is the reserve site, this could do the same job as the main site but was intended only as a backup in case the main site was put out of action for any reason. It is much more compact; the bunkers, being of a later design, are much smaller. Also to be seen is a small compound of red-brick buildings immediately beside the road which was the technical and administrative site. These buildings housed technical and maintenance workshops as well as offices for the general administration and running of the station. A typical CH station such as Tannach would have required some 142 personnel to run it, 20 RAF & 19 WAAF on operational duties and 64 RAF & 39 WAAF on admin and ground defence duties. Two LAA gun batteries as mentioned earlier protected the site. The CH stations provided a basic early warning capability but they had several drawbacks, they were unable to provide cover at altitudes below about 3000 ft. and had poor directional ability. Rapid technological developments soon produced a much smaller directional type radar that had a similar range to the CH equipment but was sensitive at lower altitudes, down to several hundred feet. The transmitter and receiver aerials were incorporated into a single antenna array which could be rotated to send out a directional beam of radio energy and were the true forerunner of modern radars. These were called Chain Home Low (CHL) radars and stations were constructed to extend and supplement the existing CH stations. CHL stations were built at Navidale, Ulbster Hill and Dunnet Head.

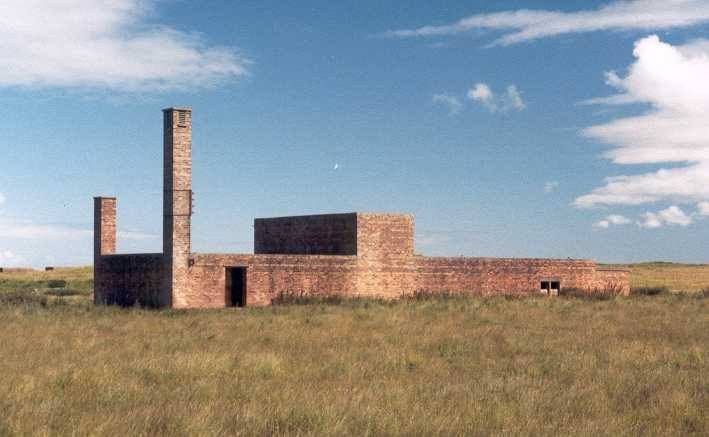

The Ulbster station is still remarkably complete, retaining all its original technical buildings. CHL stations had their Tx and Rx equipment housed together in a single building, the Tx equipment being housed at one end and separated from the slightly larger Rx/operations room at the other by a small office. The 20ft. radar gantry was situated immediately to one end of the building and the concrete feet for this are still visible. The stand-by set house sits close by and a smaller backup generator building stands at the other end of the site. There was also another type of radar installed here, designed to operate at surface level for monitoring shipping, designated as Coastal Defence (CD) radar. This was even more compact and operated from a single nissen hut with the small aerial mast mounted nearby. The base for this hut and mast stand on a hummock just south of the stand-by generator house. A typical CHL station such as Ulbster would have required only some 74 personnel to run it. 6 RAF & 19 WAAF on operational duties and 33 RAF and 16 WAAF on admin and ground defence duties. Ulbster would have had some extra to operate the CD equipment as well. The CHL station on Dunnet Head followed exactly the same design, with the Tx/Rx block and the mounting piles for the radar gantry at one end; the latter are still in good condition. Just below the viewpoint to the east by the helipad are some concrete hut bases which were connected with the mobile Naval CD radar equipment which was also sited here. Other Sites A number of wireless stations were set up in the county, mainly to provide communications for aircraft operating from the airfields here. One at Tansfield for Castletown based fighters and one at Hill of Harland, near Wick, for Wick and Skitten based aircraft. The site of Hill of Harland VHF station later became the site chosen for the construction of a Rotor plan radar station. In the late 1940's it was decided to re-assess Britain's early warning air defence scheme. From this the 'Rotor' plan was developed and a network of stations around Britain, equipped with the new Type 80 radars, was proposed. Hill of Harland was chosen as one such site. The station was built in 1954 but the equipment was never installed. Technology had moved on so fast that the station had become redundant before it was even commissioned. Apart from the radar related buildings the site also boasted a large modern operations room, the last remnants of this prefabricated structure blew away in gales early in the year 2000. In addition there were secret wireless interception stations at Bower and Noss Head and a Gee station on Burifa Hill at Dunnet Head. Gee was an electronic radio navigation aid to enable aircraft to accurately plot their position. Gee consisted of clusters of three or four stations spaced roughly 100 miles apart, one of which was designated a 'master' station, the others as 'slave' stations. The master station transmitted a pulsed signal, which was picked up by the slave stations and re-transmitted with a short time delay added. The navigator in the aircraft picked up these signals on a special receiver that used the information of time delays plotted on a special chart to triangulate on the Gee stations and obtain the exact position of the aircraft. When Gee was later superseded by the American Loran system, which is still in use to this day, RAF Burifa Hill was adapted to become a Loran station. The station operated until shortly after the end of the war when it was put on care and maintenance until the 1950�s when it was finally dismantled. The buildings were almost entirely made up of nissen huts and similar type buildings and consequently very little now remains except the red brick blast walls that protected the Tx and Rx huts and the stand-by set house. As with the radar stations, function was duplicated so there were two Rx hut enclosures and two Tx hut enclosures. Set beside each of these enclosures are the four great concrete bases for the 240 ft. wooden aerial masts and nearby are the small octagonal plinths for anti-aircraft guns as described earlier. There was an extensive domestic site beside the road just below the station which provided accommodation, ablutions, canteen and recreational facilities for the personnel as well as administration offices, garages, workshops and even a cinema. These were all of nissen hutting and, like the operational site, are now all long gone. Noss Head and Bower were probably two of the county's most secret and clandestine wartime sites. Bower was a radio direction finding (D/F) station, originally set up by the Royal Navy, its purpose was to locate the source of German radio transmissions by triangulating with other similar stations around the UK and Greenland. The station continued to operate after the end of the war and in 1967 its operation was taken over by GCHQ who continued to expand its operations here throughout the cold war. Little information is available as to Bower's role within GCHQ as its operation is still covered by the Official Secrets Act and former employees are reluctant to talk about their involvement. The station finally closed in 1977 largely as a result of the increasing transfer of communications technology from radio to satellite. The main compound at Bower has been cleared and is now used by Norscot. The main Rx site at Reaster has recently been de-requisitioned and sold back to the owner. The post war GCHQ era operations room here is still intact as is one of the large aerial arrays. The Noss Head station was equally secret, its purpose being the interception of German radio traffic, most of it in the form of the five letter grouping of the Enigma code. There is little of this site left, the only reminder of the wartime use is a brick blast wall in the far corner of the site, which protected one of the small receiver huts. The iron mounting brackets for the aerial masts can also be found sticking out of the ground. The two existing buildings are post war. Information from both of these stations was passed to Bletchley Park in Bedfordshire and made up part of the data that helped produce the now famous 'Ultra' information which made such a significant contribution to bringing about the end of the war. Passage of all service personnel to and from Orkney, (Navy, Army and RAF), except those arriving directly aboard their ships, was through Scrabster. Their movement was organised by No. 27 Embarkation Office with HQ at Mina Villa house in Thurso. Between the dates Feb 1941 � Feb 1946 this office records dealing with the movement of nearly 125,000 personnel. To accommodate the hundreds of thousands of service men and women who came through Thurso on their way, via Scrabster, to and from Orkney and beyond, a large transit camp was built on the western edge of the town. Nothing remains of this except the main entrance gate opposite Pennyland Farm, with a length of tarmac road and a small concrete hut beside the gate. Towards the end of the war a camp was built at Watten to house German prisoners of war. The camp was situated at the north end of the village where a football field and new housing estate now stand. A single concrete generator building at the back of the houses is all that remains of the camp. This is necessarily only a brief overview of some of the aspects of Caithness part in WW2. . I am only just beginning to investigate these aspects such as the roles of the Civil Defence, Home Guard, ARP, police and fire departments, not to mention the Royal Navy presence in the county. I hope to bring to light something of their contribution in the near future. If any readers have information or comments concerning the sites mentioned here, or indeed any aspect of the wartime military activities in the north of Scotland, I would be delighted to hear from them. Addendum to the above article. Giles could have entitled his carton

- |